The natural resource addressed in this section is that of ambient sound, or "natural quiet", a term coined by the National Parks Service to describe an indigenous characteristic and hallmark of rural and wilderness areas. 1 The residents of western Boulder County's mountain communities have enjoyed a long history of minimal impact from pollution, both air and noise emanating from Colorado's growing Front Range commerce and industry.

While the focus of this section is noise pollution, the fact is aircraft engines are significant producers of many types of toxic pollutants. Unlike many sources of industrial pollution, airports are not monitored and regulated to protect the environment and the public's health and well being from resultant noise, air, soil and water pollution. The Natural Resources Defense Council reports that while air pollution totals from automobiles and many major industries have stabilized or decreased over time as a result of stricter emissions policies, aircraft continue to emit more and more toxic pollutants, such as carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, lead and nitrogen oxides that contribute to smog and respiratory problems with long-term health and other environmental implications (Natural Resources Defense Council 1996). It has also been reported that aircraft emissions are responsible for one-half of the man-made atmospheric nitrogen oxides (Skelton, R 1996).

Ambient noise levels in rural mountain settings with no aircraft overflights are typically inaudible, falling below 20 decibels as per A-weighted scale abbreviated dBA. 2 Jets arriving and departing from Denver International Airport (DIA) often register as high as 80 dBA on sound level meters located in these rural areas more than 50 miles away.3 Following the logarithmic nature of sound measurement, this aviation noise amounts to a perceived increase over ambient noise by a factor of 64 times, resulting from a 1,000,000 times increase in the power generated by aircraft engines.4

|

| Figure 10.1 Relative Noise Levels: Downtown Boulder, Magnolia Rd., Indian Peaks Wilderness. |

In 1989, before DIA was built, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued the results of an Environmental Impact Statement that read in part:

"Given that the proposed new Denver airport will be approximately 13 miles northeast of Stapleton (in other words further away from Boulder), aircraft...will over fly Boulder in about the same areas they do now...noise (from aircraft departing from and arriving at the new airport) heard in the Boulder area will be somewhat lower than the already low noise levels from Stapleton overflights" (FAA 1989).

During the planning of DIA, Boulder County citizens and government officials were assured that they would not experience additional noise as a result of the new airport, and were, consequently, excluded from the planning process. 5 These same parties concluded that there was no need for concern in light of this assurance, and the County's distance from the new airport. The promise stated unambiguously in the FAA's Environmental Impact Statement has been violated every day since DIA's opening. (Boulder County Commissioners have stated that the Environmental Impact Statement has no “legal” value.) In its first three years of operation, DIA has led the nation in the number of noise complaints registered by angry citizens each year (Daily Camera 1996). In late 1997 the DIA Noise Abatement Office reported to BC CAAN that there are approximately 1,500 daily operations and that the eventual "full build out" of the airport will double this capacity.

It is estimated that 20 million Americans are exposed to noise levels that can lead to psychological and physiological damage, and another 40 million people are exposed to noise levels that cause sleep or work disruptions (Staples 1996). Chronic exposure to noise has been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular health problems, strokes and nervous disorders (Cohen et al. 1981). Resultant sleep deprivation and task interruptions pose untold costs on society in diminished worker productivity (Fry 1991). Recent studies have pointed to the negative effects of noise on children's abilities to concentrate on school work (Bronzaft 1997). The deleterious effects of human-made noise on wildlife is less clear but observations support that sudden increases in ambient noise may interrupt mating processes, feeding, and may also cause psychological stress that affects hormonal levels and the incidence of disease (Orion 1996). In addition, the amounts and effects of other aviation pollutants such as engine exhaust and de-icing by-products raining down on the earth is just now being questioned and seriously studied (Natural Resources Defense Council 1996).

|

|

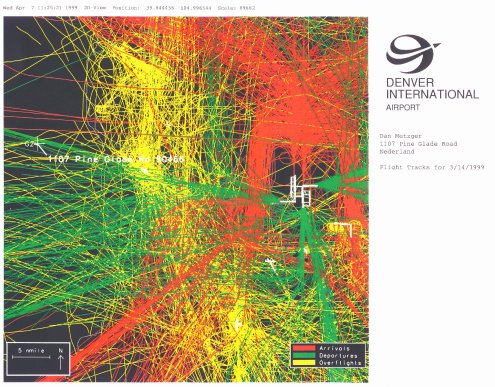

Figure 10.2 A single day of DIA

flights

|

At the time of this writing, Boulder County does not have any policies that address aviation noise pollution from aircraft originating outside it’s jurisdiction. Current local aviation noise standards developed by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) consist of the archaic "day-night level" (DNL) averaging technique that is primarily aimed at areas close by the airport that receive steady and loud noise throughout most of the day.6 The type of noise pollution mountain communities and wilderness areas are exposed to is more accurately described as "single event" exposures whereby inaudible naturally quiet ambient sound levels are interrupted, perhaps several times an hour, by a loud overflight that shatters the stillness of the moment. Averaging these events over the course of a 24 hour day results in numbers that fall below the 65 dB DNL FAA standard that requires remedial action by the airport.

In stark contrast with the definition of "wilderness" (Wilderness Act of 1964)7, the "natural quiet" and "primeval character" of Boulder County's Indian Peaks Wilderness, Rocky Mountain National Park and Roosevelt National Forest are shattered everyday by airplane noise, much of it originating from DIA. Along the flight corridors that cross over these areas are thousands of Boulder County citizens who have chosen to live and raise their families in the beautiful mountain communities that border these designated wilderness and park land areas.

While not directed at Boulder County, an attempt to address the aviation noise problem occurred in 1996-7, when noise abatement procedures resulting from legal agreements among Denver, DIA and Adams County were implemented. These new regulations directed noisier "stage 2" jets departing from DIA north to Wyoming, thereby gaining altitude before heading west. Airlines are preparing for a December 1999, required transition to quieter "stage 3" engines by replacing old aircraft and/or retrofitting stage 2 aircraft with euphemistically named "hush kits". While an original manufacture stage 3 engine has been reported to be as much as 10 dB quieter than stage 2, the effectiveness of hush kits is questionable. The suggestion that these retrofitted aircraft can now be considered "stage 3" is dubious. Even the current director of DIA's Noise Abatement Office admits that these retrofitted aircraft will not be perceived as being much quieter.8 If hush-kitted stage 2's are permitted to fly west, Boulder County may suddenly experience a doubling of aircraft traffic. DIA officials plan to evaluate how much quieter hush-kitted Stage 2 aircraft are and make a determination as to how many of these converted airplanes will be permitted to fly west.

In 1997 the City of Denver bankrolled a major share of a new organization that studied DIA noise issues. This organization, bringing together elected county officials and citizen representatives from communities negatively affected by DIA noise hired consultants to interview people in noise-impacted areas and to document sound levels. In early 1998, a report with recommendations regarding flight path modifications was delivered to the organization and then directed to the FAA. For no apparent reason Boulder County was dropped from this study, even though the County contributed financially to the study group (see Appendix 10.6). At this time, the FAA has issued no clear statement of support for this organization and no assurances that they will act upon any of the recommendations. An unfortunate result of this "new organization" has been the deactivation of the DIA Noise Task Force and the Noise Forum, two vehicles for public recourse created by DIA administrators shortly after the airport opened.

|

|

Figure 10.3 DIA flights over Indian

Peaks Wilderness area on Sept 2, 1999.

|

Numerous interviews with Boulder County's rural residents during 1996-1997 support the fact that before DIA opened, airplane noise from Stapleton Airport was minimal, noticed by some people on the average of 2 or 3 times over the period of an 18 hour day.9 After DIA opened, frustrated citizens were logging as many as 60 noisy overflights over the same daily time period.10 In April of 1997, citizens of western Boulder County's Magnolia Road area logged an average of 30 daily disturbing overflights ranging in sound intensity from 55 dBA to 75 dBA, with occasional events approaching 80 dBA.11 The citizens of Boulder County have seen inconsistent relief from aviation noise pollution. Routes have been adjusted to comply with legally binding contracts that were made between Denver and Adams County.12 Boulder County has benefited somewhat by these route adjustments, and citizens' observations point to "traffic shifting" that results in some days being quieter than others. Many Boulder County residents continue to phone in noise complaints to the DIA Noise Hot Line but receive no feedback. DIA officials proudly point to smaller numbers of complaints (see Appendix 10.3, DIA Quarterly Noise Reports). The truth is...many citizens have given up calling the Noise Hot-Line. As confirmed by conversations with citizens groups across the country, the FAA strategy of wearing down the public works. An active and constructive dialogue between citizens and DIA officials does not exist. Discussions with Boulder County Commissioners and DIA administrators have led the public to conclude that there is presently no recourse for County citizens impacted by DIA (and other airports) and that there is little, if any enforcement of airline infractions of established noise abatement procedures.

The aviation industry remains the largest unregulated industrial polluter in the world. The Noise Control Act of 1972, and the Quiet Communities Act of 1978, directed the federal government to protect public health from the adverse effects of noise. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was charged with overseeing these acts and established an Office of Noise Abatement and Control. Funds for this branch of the EPA were terminated in 1982. Since then, the FAA's mandate to "promote the aviation industry in the USA" has consistently overshadowed environmental and quality of life concerns.

Pending and future Federal legislation offers promise of relief for millions of Americans who have for decades been battling the FAA and local airports to reduce aviation pollution. The "Quiet Communities Act of 1997" (House Resolution 536 and US Senate Bill 951) was introduced by Congresswoman Nita Lowey of New York and co-sponsored by many legislators, including Colorado 2nd District Congressman David Skaggs (see Appendix 10.5 for a summary of the bill). The Quiet Communities Act of 1997 would have taken away oversight of aviation pollution issues from the FAA where there is clearly a conflict of interest, and would have returned the responsibility to the Environmental Protection Agency. As stated in the act, the EPA would have had the authority to study, revise and enforce standards pertaining to noise, air, soil and water pollution caused by the aviation industry. Unfortunately the bill was defeated. Future legislation includes a revised Quiet Communities Act, as well as “The Silent Skies Act”, being developed by Congressman Mark Udall. This new legislation will support much needed research and development of cleaner and quieter jet engines.

There are clearly four tiers to the aviation pollution problem:

Only by assuming an interdisciplinary approach can a solution be found that acknowledges the importance of our country's commerce and industry without sacrificing the earth's ecosystem and the health and well-being of its inhabitants. All contributors to the problems must work together to seek solutions. The passengers can fly less and demand cleaner and quieter airplanes from the airlines while rallying for high speed rail from their local governments. The airlines can demand cleaner engines from their suppliers. The manufacturers that serve the airline industry can devote more attention and resources to producing environmentally friendly products. Our federal government can support all of these efforts while enforcing existing regulations and enacting new ones that protect our health and quality of life.

It is time for Boulder County to create a "quality of life" vision for the future by enforcing existing policies, enacting policies supportive of the environment, public health and well-being, and demanding accountability from all levels of government. The Federal government must take the lead by enforcing existing policies and enacting contemporary policies that balance the preservation of national resources (people, wildlife, clean air, clean water, clean soil, etc.) and health of the environment, with the needs of a growing population and the associated commerce. A balance of national priorities is essential to assure the sustainability of our planet into the next millennium.

PUMA is committed to protecting what remains of the beauty and sense of sanctuary of our rural mountain community, wildlife and wilderness areas, and recognizes noisy aircraft overflights as a gross form of human-made pollution that must not be permitted to continue and to grow unchecked. Since the early 1980's, the Federal Aviation Administration has policed itself in regard to the environmental impact of aviation. The study, regulation, monitoring and enforcement of aviation pollutants must be returned to where it belongs, the Environmental Protection Agency. We are hopeful that federal legislation will result in a reorganization of our nation's priorities in which the health and well-being of her citizens and natural resources will be placed ahead of, or at least equal to, the commerce and industrial factions that are poisoning our planet.

1 The expression "natural quiet" is used in the National Parks Overflights Act of 1987, regarding the Grand Canyon.

2 The A-weighted scale approximates the human ear's less sensitive response to low frequency sounds.

3 Sound intensity peaks of 80 dBA created by DIA traffic have been measured and reported by Boulder County mountain residents using their own sound level meters.

4 A doubling of sound results in a noticeable 3 dB increase in the total measured sound. A 10 dB increase is required for a perceived doubling of sound intensity or loudness. See "A Few Words About the Decibel" in Appendix 10.2.

5 During 1995-97, members of Boulder County Citizens Against Aviation Noise (BC CAAN) met with County Commissioners and staff at the Boulder County Commissioners Office. BC CAAN was told that before construction of DIA commenced, Boulder County was assured that there would be no noise impacts on the County, as supported by the 1989 Environmental Impact Statement. As a result, Boulder County officials were not concerned...until the airport opened.

6 The day-night level (DNL) is derived by measuring average sound levels in a 24 hour day. Nighttime noise, between the hours of 10:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m., is weighted an additional 10 decibels to compensate for sleep interference.

7 "A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and it's community of life are untrammeled by man...retaining it's primeval character...with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable..." (Wilderness Act 1964).

8 In telephone conversations with BC CAAN staff in October, 1997, Mike McKee, Director of Noise Abatement at DIA, candidly admitted that he did not believe that a hush kitted stage 2 engine would be much quieter, and would certainly not be as quiet as a manufactured stage 3 engine, which according to the Natural Resources Defense Council is 10 dB quieter.

9 In 1989, sound level measurements were made in Boulder County after a brief rerouting of Stapleton Airport resulted in a sharp increase of complaints. This information is on file at DIA's Noise Abatement Office.

10 BC CAAN members began logging noise events shortly after DIA opened. As many as 60 noisy overflights during an 18 hour period were logged.

11 Several Boulder County mountain residents own sound level meters with an accuracy of +/- 3 dB. Most of the loud jet passes register approximately 70-72 dBA which is as much as 40 dB above the natural ambient sound. In rare instances, a peak measurement of 80 dBA occurs.

12 Under an Intergovernmental Agreement between Adams County and Denver, the city agreed to pay $500,000 for each violation of DIA noise limits as set in the agreement. Boulder's mountain communities have benefited indirectly from some of the corrective rerouting that has occurred, such as directing noisier stage 2 aircraft north to Wyoming before turning west.

|

|