THE SCATES RANCH AND MAGNOLIA ROAD

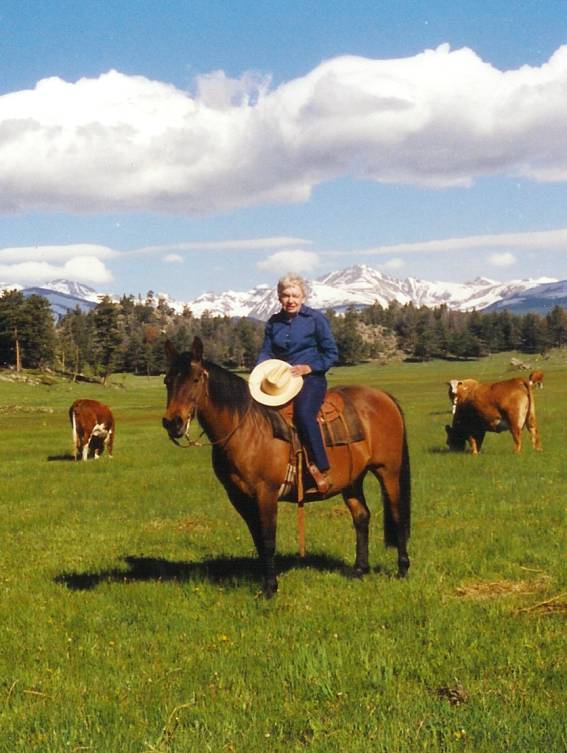

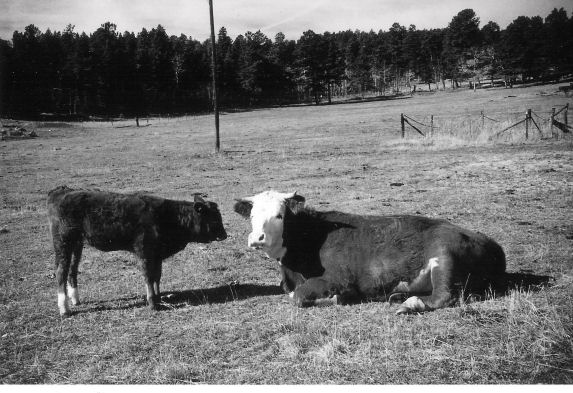

Figure 1: Edith in the Upper Meadow

CONTENTS

History of this Project....................................................................................................................

Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................

Introduction.................................................................................................................................

Chapter 1 Converging in Colorado: Wings and Scates............................................................

C. P. Wing (Granddad)..............................................................................................................

Scates Family History................................................................................................................

Chapter 2 Childhood and Beyond...............................................................................................

Edith Rose and Dick Sherman....................................................................................................

Guests on the Ranch..................................................................................................................

Edith’s School Days...................................................................................................................

Pine Glade School............................................................................................................

Mount Saint Gertrude’s Academy.................................................................................

On to Emily Griffith’s Opportunity School....................................................................

Edith’s Work away from the Ranch..........................................................................................

Why Edith Never Married........................................................................................................

Chapter 3 Ranch on the Big Hill..............................................................................................

Chapter 4 Neighbors and Friends in the Early Days..............................................................

Hetzers, Hendricks, and Dr. Bills..............................................................................................

The Giggey Family...................................................................................................................

The Betasso Family..................................................................................................................

Chapter 5 Family’s Work On and Off the Ranch....................................................................

Children’s Chores....................................................................................................................

Women’s Roles.......................................................................................................................

Food.......................................................................................................................................

Getting Electric Lights and the Radio........................................................................................

More Ranch Responsibilities....................................................................................................

Hauling Timber........................................................................................................................

Working in the Mines...............................................................................................................

Chapter 6 Scates’ Cattle Ranching..........................................................................................

Cattle Ranching........................................................................................................................

Summer Range........................................................................................................................

Making Hay.............................................................................................................................

Chapter 7 Getting Around the Magnolia Road Area..............................................................

Roads......................................................................................................................................

Magnolia Town and School......................................................................................................

Getting to Town.......................................................................................................................

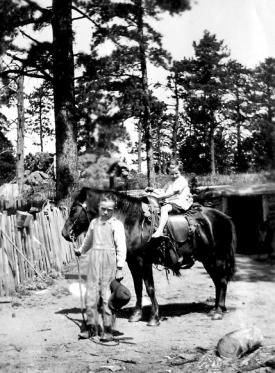

Horses at the Ranch.................................................................................................................

Getting the Mail.......................................................................................................................

Getting the Family’s New Car..................................................................................................

Chapter 8 Mountain Fun...........................................................................................................

Dances and Plays.....................................................................................................................

Holidays..................................................................................................................................

Fishing, Hunting, and More Fun................................................................................................

Appreciation of the Natural World...........................................................................................

Chapter 9 Community...............................................................................................................

Membership in Organizations...................................................................................................

Spiritual Life and Picnics..........................................................................................................

Chapter 10 Conclusion............................................................................................................

The attic of the Scates’ Ranch home harbored many family photos, taken through the decades, and Edith’s collection of color slides from 1959 to 1973. Marianne Stilson had the idea that she, and others, would be interested in learning more about those pictures and about life on the Scates’ Ranch. Marianne enlisted Marie Mozden, a long-time friend of Edith and Dick Scates, to help Edith locate the slides, so the history only Edith could provide would not be lost.

Having those slides in hand, Marianne told neighbors, Bonnie Sundance and then Jan Kuepper, of her wish to create a presentation of Edith’s pictures, with Edith as narrator. In January 1999, the three began meeting to review the slides and consider the possibility of creating a slide show, a video presentation, or a published booklet.

They arranged to go to Edith’s home on the evening of April 19, 1999, carrying a potluck supper and equipment to show the slides and to record Edith’s comments. Although shy about being recorded that first evening, Edith joyously welcomed Marianne, Bonnie, and Jan at her kitchen door (Figure 2: Marianne, Edith, Jan, and Bonnie). After supper, the group gathered around her in the living room. George Giggey stopped by daily to give Edith “her meds” and he stayed on to view the slides.

Edith quickly adapted to the plans to show her slides. She was patient as she was bombarded with question after question about her life and the Scates’ Ranch.That was the first of many similar gatherings in which the ninety to ninety-three-year-old Edith Scates always showed wondrous good spirit and did her best to jog her memory as accurately as she could.

Julie Harris, a long-time friend of Edith’s, with a strong interest in the history of the Scates’ Ranch, joined the group in July 1999 (Figure 3: Edith, Marianne, Julie, and Jan). Julie was Edith’s primary caregiver during the last year of Edith’s life. During that time, Edith shared personal recollections with Julie. This additional information enhanced the project.

Marianne,` Julie, and Jan proceeded to write out all of Edith’s words after having the audiotapes transferred to CDs. Transcriptions of the CDs facilitated organization of the material into thirty-six topics, using “cut and paste.”

In 2002, Julia Chase (a near neighbor) became an active worker in the project. Julia’s experience researching land title and historic records of Boulder County was of great value. Her enthusiasm spearheaded the effort to conclude the project in the summer of 2003.

In addition to the extensive interviews with Edith, the group made substantial use of other transcribed comments Edith and her brother, Dick, made during tours of the area in 1982 and 1984. It was Barbara Poppe, Margaret McGinnis-Stockton, and Linda Armour who established the routes and audiotaped their comments. The five traveled the entire length of Magnolia Road, from Peak-to-Peak Highway to Boulder Canyon. Those transcripts provided us with the only record of Dick Scates’ exact comments, and they were used extensively in this booklet.

The project members, calling themselves the Edith Scates Memoirs Group, originally planned that their end result would be a slide show narrated by Edith.As their innumerable interviews and work sessions progressed ( Figure 4: Marianne, Jan, and Julia), they began to envision a video program as their creation to be shared. Not having the required funds or know-how for video work, they came to the conclusion that a tangible booklet, to be owned and held, would be the best way to share the history they recorded. This is that booklet.

Figure 2: Marianne, Edith, Jan, and Bonnie

Figure 3: Edith, Marianne, Julie, and Jan

Figure 4: Marianne, Jan, and Julia

Many people were kind and helpful to us as we planned and completed The Scates’ Ranch and Magnolia Road. We would like to say a special “thank you” for the following contributions:

· PUMA (Preserve Unique Magnolia Association) provided full financial support for the printing of this booklet. Carli Zug also contributed financially to the project expenses.

Storytelling offers an important dimension to the understanding of the past. Years ago, it was the old ones who were our storytellers, and it was through their storytelling that wisdom, history, values, and lessons were passed along. They made it a point to remember as many details and events as possible. Like the old ones, Edith’s stories (as we have documented them) will pass along insights and details about the Magnolia area, the people who were part of the drama, and the events that directed their lives.

For us, the members of the Edith Scates Memoirs Group, writing this booklet has been a labor of love. Here, we would like to share some of our memories of Edith.

Edith was a kind, ethical, humble, capable, resolute, and wise woman. Here’s one example of advice she shared: “Any fool will bring a coat when it’s cloudy. A wise man will bring one when the sun is shining.”

Gathering at Edith’s for supper was always pleasant. We, the memoirs group, will not forget how happily she welcomed us. When it was time to serve dessert, she once commented, “You should always eat dessert first. No one wants to skip dessert. So, they always eat it no matter how full they are. Then, one ends up with too full a stomach. If you eat dessert first, that won’t happen.” Edith’s favorite dessert was lemon meringue pie. As we planned a gathering for her ninety-first birthday, we asked her what kind of birthday cake she’d like. She thought a bit, and replied, “I really like lemon meringue pie, not too sweet.” For her last two birthdays, we served her lemon meringue pie. In fact, it was the last food Edith ate before she passed away.

We will remember her laughter. One of her slides showed a cowboy lying in the grass, eyes closed, his cowboy hat blocking out the sun, and beer cans littered around him. She gave a hardy laugh recalling how the men in the group placed the cans around the victim while he was napping. She also chuckled as she told us, “On Saturdays, they would take their baths, with the cleanest ones going in first. Then, when the dirtiest ones came along; well, they had to go in last.”

She found great joy watching the rabbits, birds, and squirrels on her porch. Edith even named an especially voracious squirrel “Fatso.” Often, she giggled in delight, as a young child would.

Edith had a distinct way of story telling. She often began, “Well, now, let’s see . . .” drawing the words out. We remember how she would tell tragic stories, such as the ones about Shannon Looney being struck by lightning; the dead dog tied to the tree; and the murder of her good friend, Emily Griffith. Edith would speak quietly and slowly. We would be hanging onto every word. Then, she would suddenly come out with the shocking ending. She was a fine storyteller.

The memoirs group was entertained and inspired by the knowledge and experiences Edith carried with her. She cared deeply about the ranch land — it’s past, present, and future. Edith always welcomed neighbors and friends to the ranch. Many of those neighbors live on the land that was once part of the Scates’ Ranch. This has been her story of living, thriving, and surviving there during the twentieth century.

At sunset one day, the memoirs group drove with Edith to “the back meadow” and looked at the ranch with Mount Thorodin in the distance. Sitting quietly in the car, with the sky aglow and peace all around us, we remarked how this was a little piece of Heaven on earth.

When her mother (Eva Scates) became gravely ill, Edith cared for her, taking her to Denver for medical treatments. Eva died in 1969, and her last words to Edith were “thank you for taking such good care of me.” Edith made this observation of her mother’s last days: “She was able to be here, where her home was. Her heart was in this land, and she had spent her life on Magnolia Road.” This was also true of Edith’s own life.

Figure 5: 1880s Homestead (foreground) and 1920s House (background)

In 1874, Charles Phialandrews (C. P.) Wing, Edith Scates’ maternal granddad (Figure 6: Scates and Wing Family Tree), made his way on foot from Wyoming to the mining towns in the Colorado Territory. A sawyer by trade, he hoped to find a market for timber and lumber at the mines. C. P. met and married Adeline Hurley, a miner’s daughter from Central City. They had nine children. In 1887, their second child, Eva May, was born. They moved to the Magnolia area when Eva May was 6 months old. Eva’s younger siblings were born in a shack next to one of C. P.’s sawmills (Figure 7: Magnolia Road and Surroundings).

Dick Scates described it this way, “Wherever there was water and a grove of trees, there was a sawmill. My granddad ran a sawmill with a little steam boiler and engine over two gulches [at Kellogg’s].” It was better to move the sawmill where the timber was, so you could skid [to haul by dragging] it right into the mill. “The sawmills were temporary shacks. They knew they wouldn’t be there long. The houses were made just the same. Anyway, they’d just throw up a frame and nail some sides up and freeze all winter. The family was right there, all year round.”

C. P. bought a 160-acre homestead, with a house, located near the Front Range Trails. The homestead was on both sides of Magnolia Road. Dick recalled, “East of there was the Pine Glade schoolhouse and the teacher’s house. You can still see some of the schoolhouse foundation.” Dick described another house, “Granddad and Mother’s family lived down at the old sawmill down across the gulch (Kellogg’s place). There’s nothing left of it now. The kids had to work in the timber business long before they should have, the boys especially. Granddad didn’t have any education and he didn’t see any use of the kids spending time in school.”

A great deal of the work at the sawmills depended on the help of C. P.’s family members. Edith recalled, “I remember Granddad ran a sawmill a ways from my place. He had an awful bad temper. His outburst of temper and sometimes his treatment, especially of the boys, I felt was quite unreasonable. If the boys saw him coming, they’d go to avoid him. Like people who do have bad temper, they don’t use much reason. They just flare up. I know later in life how much he regretted that. He said, ‘I could have been such a pal to my boys’.”

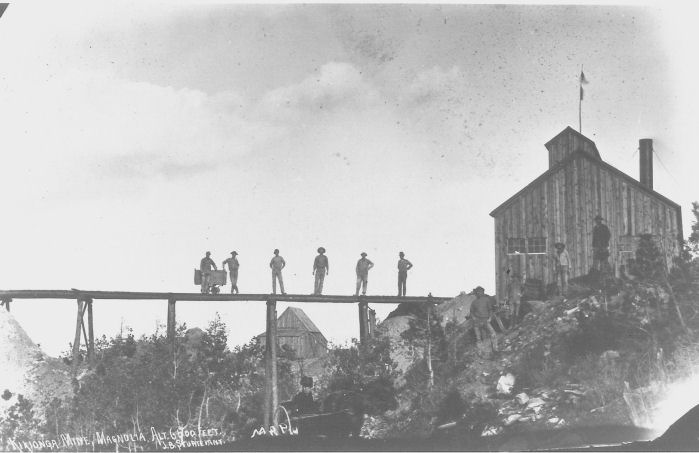

As early as 1890, C. P. was operating one of the sawmills at the junction of the present County Road 68 and Aspen Meadows Road. Unlike agriculture, sawmills proved to be the right choice at the right time. Well into the 1940s, the mining industry needed lumber, mine props, and railroad ties. C. P. installed a telephone at his sawmill located near the Kikionga Mine. Dick Scates explained, “Granddad had a sawmill in the next gulch above Marie’s [Mozden]. He had a telephone. But, of course, they ran the line from tree to tree. They didn’t set poles or anything. My granddad had it there to take orders for the sawmill. I guess Dad could of had one, but he didn’t want it for fifty cents a month.”

The sawmill business presented enormous challenges. Nowhere were there easy guidelines to follow. C. P.’s philosophy was to always endure tough times, be self-reliant, and to depend on no one outside the family. As Wallace Stegner wrote in Wolf Willow, “ . . . [H]e had to contain within himself every strength and every skill.”

Figure 7: Magnolia Road and Surroundings

The first of the Scates family to move to Colorado was Edith and Dick’s father, Sherman William Scates. He was born in the early 1870s to William and Miriam Scates (Figure 6: Scates and Wing Family Tree). William and Miriam homesteaded in eastern Kansas. While William was in the Civil War, he marched with General Sherman from Atlanta to the sea. That is why William and Miriam chose the name “Sherman” for their son. Sherman was only eight years old when his father died.

Edith recounted that her father did not go to school past the third or fourth grade, and he taught himself after that. When Sherman was about sixteen years old, he moved to the ranch on Magnolia Road to live with his Aunt Agnes and Uncle George Seal. Agnes was his mother’s sister. They lived in the homestead cabin that still stands on the ranch today.

Before Agnes and George were married, Agnes and her sister, Maggie, ran a boarding house in the town of Magnolia. George was a miner there. Agnes and George married in February 1889, and then moved to the ranch. However, George was away from the home about six days a week working in the mines. Agnes was pregnant and tired of “living alone,” so she sent money for her nephew, Sherman, to move to the ranch and help with the work. Edith remarked, “I don’t know how much good they thought a sixteen-year old boy could help [with the pregnancy]. [Sherman] must have come on the train, then probably walked the rest of the way.” He was a help with the chores around the homestead. Edith said that her father “worked in the mines some, but he was always much more interested in livestock.” Sherman eventually ran the ranch for his uncle.

In 1890, Sherman’s Aunt, Agnes Seal, died while giving birth to Agnes Coline Seal. When Agnes Coline was seven, her father died of pneumonia, and she inherited the ranch property. Sherman, who was already running the ranch, was appointed as her executive guardian. However, Agnes Coline was raised in Boulder by her Aunt, Maggie McClure.

Sherman Scates also worked for C. P. Wing cutting cordwood for mills and wood stoves. When one of C. P.’s sons (Gus) caught pneumonia from playing in the wet sawdust, C. P. asked Sherman to fetch Dr. Bochman in Rollinsville. Sherman brought the doctor to the Wing’s house, and that is when he met Eva May, one of C. P.’s daughters.

Eva May Wing was born September 14, 1887. Edith said that her mother went to school until about the fifth grade. Eva had one older sister, Dora, and seven younger siblings. Dick recalled, “They [the Wings] had a whole slough of kids and Grandma wasn’t very well, so Mom had to stay home and help with the family.” Eva brought up her younger siblings.

C. P. encouraged the match between Sherman and his daughter, Eva, even though Sherman was eighteen years older than she. Edith figured that C. P. thought that a chance for his daughter to marry a well-to-do rancher was probably better than her life at home. Sherman and Eva were married in Central City by a justice of the peace on January 17, 1906.

Eva was twenty when Edith Rose was born in 1907. Richard was born in 1909. Both children were delivered on the Scates’ Ranch in the small homestead house where the Scates family lived.

Edith Rose Scates was born November 11, 1907, in the old homestead house (Figure 8: Homestead House). Dr. Bochman, from Rollinsville could not be reached in time for Edith’s birth. Therefore, Edith’s parents managed the delivery. Not having been experienced in delivering a baby, Edith’s father tugged at her little body. For the rest of Edith’s life, one hip rose higher than the other. She referred to her hip trouble as a birth defect. Her Grandmother Wing helped name her Edith Rose, because she especially liked the name “Rose.” Richard Sherman Scates was born two years and ten days after Edith. A woman from Nederland, Mrs. Sloughenhoff, cared for Edith while Dick was born.

Edith described herself as “timid and well-behaved.” She remembered clearly that “Dad was pretty severe with discipline if a youngster misbehaved.” Edith especially liked to play on the flat rock, now in the backyard of an adjacent house, because she so enjoyed the beautiful view from there. Leisure time, off somewhere, was probably very special to Edith, because she had a lot of chores and responsibilities, even when she was a little girl.

Fondly, Edith spoke of the family dog, Bootsie. “He wasn’t a very good cow dog, but our Bootsie was the very best pal you ever had. Yes, he seemed intelligent, and he loved us very much, but as far as driving stock or anything, he never seemed to catch on. He would always go for the head, and a stock dog has to go behind to drive because if he goes for the head, he just turns them away and is more trouble than he is good. He lived to be about thirteen, and then the coyotes killed him, or he may have lived longer.” The family also had a blue heeler, a breed well known for herding skills.

Reminiscing about her young aunt and their bedtime stories, Edith said, “Blanche was my Aunt, my mother’s youngest sister. She was just five years older than I was. Blanche lived with us on the ranch. Blanche and I made ‘a pretty good team for play’.” She continued, “Almost every night in the winter, Blanche, Dick, and I would go to bed and get under the warm covers, and Blanche would read to us. We liked to hear her read Zane Grey, Jack London, and magazines with romance stories.” Edith’s mother read The Bible at home.

As young teenagers, Edith shared many adventures with her Pine Glade School friend, Lorraine Schlick. “We each had a horse, and we’d go out a lot. We went up above Eldora, up around Hessie, way up toward the Snow Range. We took long rides over on Mount Thorodin too. I remember, once Lorraine baked a gooseberry pie out of wild gooseberries. Oh, so sour. Oo-oo-oo! We went over to Mount Thorodin, up toward where the fire watch used to be, and she carried that pie on horseback, so we could have gooseberry pie!”

When asked if her parents worried about her when she went out riding, Edith replied, “Oh, I don’t think they minded. Unless the horse fell, or something like that, there wasn’t much danger. There were lots of badger holes, and you had to be careful when you were riding, because if the horse steps in one of those, he could easily break his leg. So, we had to watch.”

Figure 8: Homestead House

Figure 9 Eva, Edith, and Dick

It is clear that when family or friends needed a place to live, the Scates family opened their home. Dick summarized it by saying; “we had a lot of people in this house at times.” Edith remembered how her mother “just loved to take care of babies.” Eva would bring in any kids who were neglected. It was the joy of her life to give a home or attention to a youngster. Edith said of her father, “He always welcomed them, and he never resented [Eva] bringing in babies and children.”

Eva’s youngest sister, Blanche, was only five years older than Edith. Edith and Blanche were very much like sisters. Edith recalled that Blanche “stayed at the ranch a good deal . . . then, later she married and went to Utah.” Blanche died when her baby daughter, Myrtle, was only nine days old. Dick recalled, “When Myrtle was about eighteen months old, she came to live with us. We raised her up until she was married. Myrtle’s older brother and sister, Robert and Irene, also lived with us for a time. Irene died when she was about eight, from measles which affected her heart.”

Dick and Edith both gave accounts of several of their long-term family “guests.” Their mother’s eldest sister, Dora Wing Turner, had twin boys, Delbert and Albert, who were born around 1904. The twins “stayed with us for a couple of years, while their mother was leaving her husband. They were about fourteen when they came to live with us. They had their work to do, and they were very good to us. They had clashing personalities, and would nearly kill each other, but they were very considerate to us.”

Dick and Edith also told about friends who stayed with the Scates. Some, like George Giggey, remained especially close to the family. Dick told it this way: “After George Giggey’s mother died, he lived here when he wasn’t working somewhere else. He lived here from sixteen until he got married. We kind of took care of him. George was a heavy equipment operator from the beginning.”

Edith said people came to visit her family more than they went to visit others. “My father’s people lived in Missouri, and we did go back there a time or two to visit, but usually, because the weather is so miserable back there . . . so hot, so they came here for the summer. We used to have an Aunt who’d come and stay all summer: Aunt Louise. Aunt Agnes and her daughter came to visit us most every year too.” Edith told of visiting back and forth with Marjorie, who “lived down on the Lower Place for a long, long time, and then she married and went to California.” Edith missed her a lot.

Figure 10: Pine Glade Schoolhouse (Illustration by Bill Border)

Before Edith was of school age, the children in her area attended a little schoolhouse on the Giggey Ranch. During 1912 and 1913, a new school was built to serve the Pine Glade-Pinecliffe area. Records show that the builder, a Mr. Allensby, was paid $106 for his work on the school. It was erected on a site which is now near the entrance to the Front Range Trails (also known locally as the Boy Scout Trails). Edith’s maternal grandparents, C. P. and Adeline Wing, had donated land for the new school. The lumber to construct it came from the Wings’ sawmill, just down the hill from the school site. This 1913 school served the area for many years before it was closed. Around 1970, it was moved to the grounds of the Nederland Community Center, not far from the place where the larger, white, old Magnolia School, had been set down earlier. Now, both schools are still standing near the Community Center. The old Magnolia School is used for art classes. The old Pine Glade School is now a private home.

(Illustration by Bill Border)In 1913, Edith went off to first grade at the new one-room, “two window,” school (Figure 10: Pine Glade Schoolhouse). She was five years old, going on six, when she began trekking the two miles to school. That first year, Miss Mae Fullmer was the teacher. She was paid $50 a month. The school board was responsible for providing housing for the “schoolmarm.” Edith told it this way: “Our teachers had to board around with different parents. Later they built the teacherage, which was such a good thing, ‘cause then the teacher could have some independence.” In 1925, the Pine Glade School teacher’s cottage was built just several yards west of the school. “It was a little, brown-shingled teacherage with two rooms.”

One can still visit the original school site and even trace the imprint of a small woman’s high-heeled boot on the steps that lead to the school door. As Edith tells it, that shoe print belonged to Vera Shipman. Vera had a cabin just southwest of the school, and some teachers boarded with her because of her cabin’s being so close to the school.

Edith shared her memories about hauling spring water up to the school: “The spring was downhill from the school. I don’t know why they always built houses, and such, so that you always had to carry the water uphill! The teacher had to haul the water. We had a bucket of drinking water at school. Everybody drank out of the same dipper. Then later, we got drinking glasses, so each person had their own glass.”

Edith remembered several of her teachers. One was Miss Mamie Latronica, who Edith thought might have been from Louisville. Pauline Yackey was another teacher, and she married Edith’s uncle, Jerome Wing. Another Pine Glade teacher, Vera Thomas, married Edith’s younger uncle, William Jennings Bryant Wing (Figure 6: Scates and Wing Family Tree).

Edith chuckled, saying, “Teachers usually married some local boys.”

Inside the one-room schoolhouse, “There was a blackboard at the front of the schoolroom that we did a lot of figures on.” At their desks, the children wrote on 8 x 10 inch slates, with chalk. “Usually there were two children to each desk. We had those long desks . . . two of us in one seat. That was a good place to take a noon nap, because you could stretch out on the seat. Must have been awful hard, but then, we’d do it.” There was a box woodstove in the middle of the room. Sometimes children would bring vegetables from home and add them to the pot of hot water on the stove. The result: hot soup for their lunch, to go with whatever food each had brought from home.”

There was no playground, so “we made our own entertainment. We’d play Andy Over, jump rope, climb on the rocks, and go strawberry hunting. My uncles used to take and haul things to Rollinsville. They would usually bring us a little sack of candy or something when they came by the school. That was a real treat.”

Edith and her schoolmates studied traditional subjects: reading, writing, spelling, arithmetic, history, and geography. When asked about school subjects she liked, Edith replied, “Mostly, I liked all of it. ‘Course, I liked history and geography, especially geography . . . I loved geography! I wasn’t too good in math, but I got by.” Edith recalled that sometimes there was only one child in a grade. “I remember the bigger youngsters in the higher grades would take the little ones outside and teach them. They would really enjoy teaching the little children, and it was a good experience for them.”

The school year schedule was adapted to conditions in the rural, mountain area. “It was mostly a six month summer school [June through November]. The school put on a program a couple times a year. We’d recite poetry or make up a skit. We’d have a Christmas program, but we weren’t in school during Christmas, so we’d have a program right at the end of school.” “We didn’t go in winter because they didn’t keep the roads open, and having a winter school could have been very difficult. Magnolia Road wasn’t maintained until it was a mail route [around 1940]. Snow would build-up over the winter. At times, it was five or six feet in some places,” Edith remarked.

The friendships made at school were very important. “About the only time we had any kids to play with was when we were in school.” Edith looked forward to seeing Emory, Cecelia, and Lorraine Schlick, and Charlie, Fred, and Wilma (surnames not given).

Even as a little first grader, Edith walked to school, and two years later, her brother, Dick, walked with her. She described how they took a trail that went through the fields and woods. “When we finally came out onto the road, we walked the rest of the way on the road. It was a lot steeper then than it is now. It took about forty-five minutes to get to school. It’s two miles. If you were in a real good hurry and ran most of the way, you could make it in half an hour. Occasionally, we’d ride a horse, especially if there was snow. But then you had to take care of it — put it in the barn, feed it, and water it. So, I’d rather wallow in the snow than fool with the horse.” Today, one can look downhill and see the collapsed logs of the old horse barn, which belonged to the Wing family and was used by the school students when they rode horses to school.

The trek to school was tainted by some experiences young Edith endured. She related, “I was about six when it happened. It made it hard for me to walk to school.” She was recalling the death of a young man, Shannon Looney, who was killed by a lightning strike during a wild mountain storm. Dick remembered the event well too, “ . . . [B]ack in 1914, there were two fine young fellows, about seventeen or eighteen [years old] out walking . . . down by Gray’s place. A bad storm came up, and they got under the tall spruce trees. You can still see the lightning strike on one of the trees. It killed one of the fellows, and the other one fell out in the rain and was revived. He came up to our house. We didn’t have a telephone, so Dad, or one of our uncles, went down to where there was a telephone and called the coroner.”

Edith spoke further about the site of that terrible accident, “I was just a little kid when I came down there. Dad was down there. It was in summertime, and the flies were so bad. The coroner [only] had a spring wagon. He came up late that evening. I never told my parents how frightened - how scared I was, but I had to walk past there to get to school. It was the most terrible thing to have to walk up there, knowing that young man [had been killed] there.”

Edith told of another fright that made the walk to school difficult: “Dad had put strychnine [out] for coyotes. A dog ate some and died. My dad moved the dog over there, a little ways from the trail. How afraid I was to go to school! I screwed up my courage, and I made my brother go with me, and we took some wire and wired that dog to a tree . . . Of course, he was dead. I was very much intimidated about going to school.”

While these memories stood out clearly for Edith, most of her school memories were pleasant. One reward of going to school then, as today, is the opportunity to see friends. While she seized the chance to visit with someone other than her own family, Edith also greatly valued her education. She remarked on how fortunate she felt, and how very important it is, to get an education.

If a student wished, it was possible to continue at Pine Glade School, even through tenth grade. Edith explained, “When I finished the ninth grade at Pine Glade [School], then I went to Boulder and stayed with a very dear friend [Mary Dodd] and went to Mt. Saint Gertrude’s Academy.” Opening in 1892, the Academy at Mount Saint Gertrude’s, 970 Aurora Avenue, was Boulder’s first private school. It was the vision of a Catholic nun, sent to Colorado from Iowa. Sister Mary Theodore O’Connor was dying from tuberculosis. She stood upon that hill on Aurora Avenue with two friends, and they envisioned the school. According to its catalog, the school was founded on “fresh air and sunlight, wholesome and nutritious food, regular hours for rising and retiring, and an abundance of healthful recreation and outdoor exercise.” It was a Catholic school up on the hill on Aurora. It was taught mostly by Catholic nuns. However, they did have some other teachers who were not nuns, Edith explained. When asked about her studies, she mentioned math and literature and Latin. “I didn’t care much for that [Latin],” she exclaimed, cringing, “but I suppose it helped with my English.”

Edith shared her memories about her first experiences living away from home with us. “It was such a change! At the time, the only transportation we had was horses. I came home almost every weekend. Sometimes, it wasn’t so convenient.” After Dick purchased a Model-A Ford, it was easier for Edith to come home to the ranch on weekends (Figure 12: Dick and his Model-A Ford). To be sure, the weekends weren’t filled with frolicking and lounging about, for there was always work to be done on the ranch. Edith was eager to help, as she cared deeply for her family, especially her mother.

Concluding her talk of Mt. Saint Gertrude’s, Edith reported, “[I] didn’t stay there too long, maybe a year and a half. I was too homesick.” But, Edith Rose Scates did graduate from Mt. St. Gertrude’s. Her next stop was Denver.

Edith attended Emily Griffith’s Opportunity School at 1250 Welton in Denver after finishing at Mt. Saint Gertrude’s. “It was convenient, because you could go anytime, and you could take anything you wanted to. It wasn’t like a regular school where you had schedules. Emily Griffith’s office was right off the entrance. She wanted to see everybody who came in. She didn’t have a closed office, like so many principals did. It was one of the first adult educational institutions in the country. It was wonderful!”

“Emily Griffith had her home over there in Pinecliffe, and I was very well acquainted with her and the saddest thing about it was she befriended everyone, and she befriended this man. He had a fine personality and was very intelligent. I don’t know why, but he murdered Emily and her sister. He then drowned himself in the creek [South Boulder Creek]. He was here just a day or two before he did this and said he was going to teach us to play pinochle. His name was Fred Lundy, and he taught at the Opportunity School. It was a very big shock, not only

here, but in Denver where Emily Griffith taught.” When Edith was asked if she enjoyed recalling her memories, she replied, “Some more than others.”

Emily’s philosophy is reflected in this statement:

"I want to help establish a school where the clock will be

stopped from morning ‘til midnight. I want the age limit

for admission lifted and the classes so organized that a boy

or girl working in a bakery, store, laundry, or any kind of

shop, who had an hour or two to spare, may come to school,

study what he or she wants to learn to make life more useful.

The same rule goes for older folks, too. I know I will be

laughed at, but what of it? I already have a name for that

school. It is Opportunity."

Figure 11 Homestead Entry

Figure 12: Dick and his Model-A Ford

Figure 13: Edith as a Young Girl

Most of Edith’s work years were spent on the ranch, but she did work away at several paying jobs. While taking classes at the Opportunity School, she was employed at an office in Denver. There she “did all kinds of letters and brochures for companies and a lot of the assembling and the mailing.”

In her early twenties, Edith took a job in Golden, Colorado. She told us, “I worked at Coors’ Porcelain Plant in the office some but in the plant most of the time.” In the plant, she worked “on chemical-ware, like crucibles.” After they had been dipped in a liquid glaze, they were run through kilns and baked. Often, Edith was the person who wiped-off the bottoms of the crucibles, “so the acetylene torch fibers wouldn’t stick.”

With warmth she told of living with family friends, the Meadows, in Golden. “They were very dear friends all our life — real good friends.” At the Coor’s plant, Edith remembered, “some real good friends” were Edith Schmick, Virginia VanWinkle, and the man who worked next to her on the line.

“I worked at Coors’ Pottery in Golden for quite a number of years. Then after my father became ill, why, I went home to stay with Mom and Dick. Then I stayed there afterward — stayed home.”

After returning to the ranch, Edith sometimes worked at the food stand for ice skaters on South Boulder Creek at Pactolus. She reminisced that “Alberta Malgram cooked at the skating business,” and there she worked with Melba Winks and Wendell Winks. Melba cooked, and her husband, Wendell, did “janitor work.” Melba, Wendall, and “quite a few Negro families” lived at Lincoln Hills, mostly a summer community, near Pactolus.

Thinking of the food Melba cooked took Edith back to her first experience with pizza. It was “probably in the middle ‘40s the first pizza I ever ate. I don’t think I ever had another that was that good. It really impressed me. It was so, so good!”

She recalled that folks also skated on the creek at the Espy place near Rollinsville. The Espy Ice Company cut ice on the creek for the Denver market and for westbound railway refrigerator cars, carrying perishables over Corona Pass (before the Moffat Tunnel was constructed).

When asked why she never married, Edith said, “Well, it just didn’t seem like it was ever the right time, or the right place, something like that. It wasn’t right for me, or it wasn’t right for them. Either I was too much older than the man that was interested, or it just didn’t feel like it was the right thing to do.” Edith met some men in her life. She said “some [were] pretty serious, but either I decided not to, or they did. So, there was one or two [from around here], but mostly from where I worked [in Golden].”

In the late 1860s, William J. Southland resided on the property where the Scates’ Ranch is now located. Southland acquired the land by means of the Federal Government’s Homestead Act of 1862 by which farmers could acquire 160 acres of land after five years of continuous residence on the property (Figure 14: Evolution of the Ranch).

In 1871, Southland sold the homestead to Charles Leitzman, a pioneer blacksmith and wagon repairman from Blackhawk. Leitzman raised cattle on the property. By the end of the decade, Leitzman expanded his property holdings to 480 acres (Figure 14: Evolution of the Ranch). The property became known as the “ranch on the big hill.”1

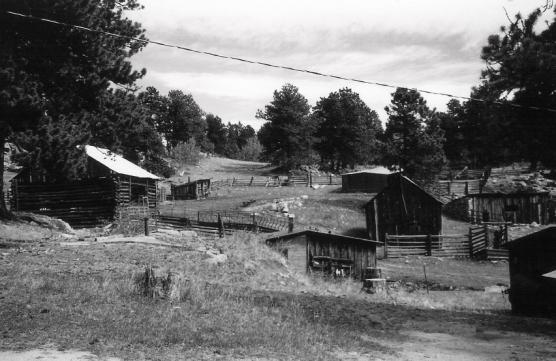

George Seal bought the property from Leitzman. George and Agnes Seal moved to the ranch after they married in 1889. Around that time, Sherman Scates came to help his aunt and uncle run the cattle ranch. By 1890, the homestead consisted of one house, two barns, two stables, one outbuilding, one blacksmith shop, and an outhouse (Figure 16: Scates’ Ranch Layout). At that time, the land was mainly used for ranching with a small part dedicated to raising crops. With high meadows for the summer and low protected areas for the winter, the land was well suited for cattle.

In 1897, Agnes Coline Seal inherited the property when George Seal, her father, died. Sherman Scates became Agnes Coline Seal’s guardian, and he continued to operate the ranch. In 1915, Sherman finally purchased the 480-acre ranch from Agnes Coline Seal [Baldwin] for $3,000. Dick said of Agnes, “ . . . [O]ld Harry Baldwin got a hold of her and that was it. Then, she was an Iowa farmer the rest of her life.” Agnes and Harry Baldwin had a son, Ed Baldwin. Ed and his wife had two children: Mary Agnes Baldwin [Mulvahill], and a son, Curt Baldwin. The Baldwin family inherited the ranch after Edith’s death.

Edith described her father as a shrewd businessman. From 1915 through 1930, Sherman bought out the following homesteads until he had purchased over 2,000 acres (Figure 15: Scates Land Acquisition (to 2000 acres)):

Parcel 1 - 1915 - 480 acres purchased from Agnes Coline Seal;

Parcel 2 - 1918 - 160 acres originally homesteaded by Enos K. Baxter;

Parcel 3 - 1916 - 160 acres originally homesteaded by Elbridge Forsaith;

Parcel 4 - 1915 - 120 acres from George Seal;

Parcel 5 - 1919 - 160 acres from Charles and Addie Wing;

Parcel 6 - 1920 - 160 acres from David Wing;

Parcel 7 - 1920 - 160 acres from Derius & Sarah Titus;

Parcel 8 - 1930 - 175 acres in the area of Gross Reservoir from Katherine Allensby; and

Parcel 9 - 1898 - 480 acres acquired from Gilbert and Rebekah Fox (originally homesteaded by Daniel Matthewson and Mark Talley).

Edith described how her father was able to buy so much land. “He bought up homesteads. People just naturally starved out. They couldn’t make a living on that little. There’s not that much agricultural ground, and there’s not the market for crops. I remember when potatoes was quite a cash crop, but not back then.” She also recalled that homesteaders “had to do so much work. They had to plant crops and probably cut some timber. They had to prove that they wanted it for a home.”

>

>

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 14: Evolution of the Ranch

Figure 15: Scates Land Acquisition (to 2000 acres)

Edith also explained how her father made the money to make these purchases. “Father hauled potatoes and coal mine props to the mines near Louisville. He cut the timber to put in the mine for the shaft. He was [one of] the first to get a herd of cattle [in the area]. One time, he furnished beef for the [railroad workers] when they were building the Moffat Railroad. So, he hauled beef over to Rollinsville.”

In 1940, when Sherman Scates died, Eva, Edith, and Dick inherited the ranch property. In 1965, they sold all of the property to developers Charles Becker, Paul Wiesner and Gerald Burkhart, except for the 175 acres that remain as the ranch today (Figure 14: Evolution of the Ranch). Dick said that they sold off the land because of financial hardship and they also had difficulty obtaining grazing permits from the US. Forest Service. Edith said they sold off their cattle in the early 1970s because “my brother’s health got so it wasn’t easy for him to do these things.” He had respiratory difficulty due to smoking and from the hay dust.

After the death of Eva in 1969 and that of her brother in 1985, Edith lived on the property until she died in 2001. In the late 1990s, Edith transferred the property into a Trust. Edith also granted a Conservation Easement to the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust, which means the property will remain a ranch in perpetuity. A new owner is not allowed any new development, except a 4,000 square foot log-cabin caretaker residence at the back of the ranch. The purpose of the easement is to “preserve the ability of the Property to be agriculturally productive, including continuing farming and ranching activities . . . and to preserve the open space character, wildlife habitat, and scenic qualities of the Property.”

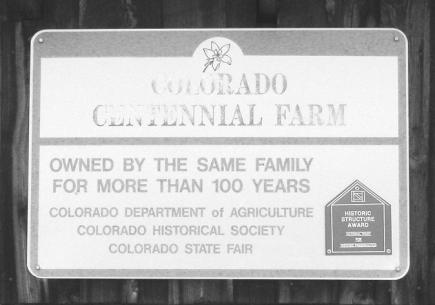

The National Trust designated the Scates’ Ranch as a “Centennial Farm” for Historic Preservation because it has been continuously associated with the Scates/Baldwin family from the 1870s to the present (Figure 17: Centennial Farm). The ranch is historically significant for its association with cattle ranching and the early settlement of southwest Boulder County. The buildings are architecturally significant for their pioneer log and wood frame construction, and because they are little changed from their historic appearance.1

The original 2-story homestead cabin built prior to 1880 is an excellent example of log structures of its time period. It is built of 14” square, hand hewn logs fastened with V saddle notch. The logs are chinked and daubed with a white, lime based mortar.1 Edith described the cabin: “Well, it had one quite large room. It was [used as] utility [for kitchen, eating and living], and [it had] only one bedroom. Upstairs, you had to stand up in the middle of the room because of the side of the room, and we had two bedrooms up there . . .” She described the upstairs as consisting of “two, kind of ‘lean-to’ bedrooms. There was really one main bedroom that could have two beds.”

Edith remarked, “When you go in, you can see where the step is worn-down, just three or four inches, from walking back and forth.” The steps that went upstairs were really worn down too. Edith remembered, “Later on, we built a kitchen onto the north [side of the cabin].” She described further, “Well, there was an old kitchen . . . where [Edith’s mother] did the cooking. It had one of those [wood-heated] ranges with the warming ovens and all.”

Figure 16: Scates’ Ranch Layout

Figure 17: Centennial Farm

Figure 18: Scates’ Ranch as seen from Magnolia Road

Sherman built a springhouse and laid copper pipe to the original cabin. There were willows there, and he used to water cattle there. Dick described his father’s project. “It was a scooped out hole and he [Sherman] thought he’d get enough water for the house, so he dug it out, but it wasn’t really successful. The spring was always flowing, but it was solid rock underneath, and they had to shoot down [blast], and sometimes when you shoot, you open a crack in the rock and the water gets away.” Dick also said that the rock around the spring was dry stacked about seven feet deep. Twenty years later, a cement cistern was put in, but it didn’t help much.

Dick, who also worked on the water pipe, commented: “We don’t need a water pump. We let Mother Nature do the pumping. The water is just a spring and runs into our holding tank.” He also recollected: “the pipe rusted out right at the beginning of WWII. We couldn’t buy pipe, so we had to carry water form over here in the gulch. There’s a well there. That got to be quite a chore when you got two feet snow. You can get used to it. You can make a little water go a long way, too.”

Other structures at the ranch included the large hay barn, saddle barn, stables, the blacksmith shop, chicken coops, and root cellar. The root cellar was built sometime prior to 1930.

Figure 19: Ranch House(Carnegie Branch Library for Local History, Boulder)

The “new” ranch house was started in 1920 (Figure 19: Ranch House>). Dick recalled, “My father, Colonel [Uncle William Jennings Bryant], [Uncle] Rome, and Clyde [Dodd] did most of the building. The logs came from and were cut at Jenny Lynn Gulch [north and east of Tolland].” Dick described the process, “[they were] very long logs, and they were seasoned, so they [the workers] just had to flatten each side and mortar. They’d had a camp up there and brought the logs down on wagons. The trip took half a day. They’d load up and bring a load down one day, then go back the next day and skid logs out for hauling the next day. Probably needed ten loads, but we [had] quite a lot of logs left over. These back logs are 38-feet long, so you had to have your wagon coupled out quite a long way. The roads were in about the same places as today but all dirt and narrow back then. If you met someone, well, one of you would have to get to a turn off and one of you would go by. That was true of Magnolia Road until about 1932 or 1933, ‘til they widened it to a two-lane road.” Dick said, “The logs were hand-hewn with a broad ax. The logs were then hatched with saw and ax, the frame put up, and chinked.”

The Scates referred to the area shown as Parcel 9 Figure 15: Scates Land Acquisition (to 2000 acres) as “the lower ranch.” It was located west of Twin Sister’s and Scates’ Mountain. This area was originally homesteaded by Dan Matthewson in the late 1870s before Sherman Scates bought it. In this vicinity, the stage stop known as Halfway House was located.

The barns on the lower ranch were built by Sherman, Dick, and Rome Wing. Dick recalled, “The timber came from Walker’s place before Gross Reservoir.” The main barn was at the bottom of the meadow under a tree. The Scates built a smaller log barn, still visible near the junction of County Road 68 and Cumberland Gap.

Dick said, “We’d store hay in the barn and have to come down and feed the cattle in the winter. There was lots of water, but sometimes on a real cold winter the water would freeze up and bulge over, but you could always get water up among those willows. We had oats planted in the field nearby, and we’d stack the oats and the elk would come down and eat the hay. So, we built that barn. There was one bad feature [with the field]. The soil was so rich, and the oats would grow so big and tall. It was awfully hard to cure them out. Really, it was a peat bog — it’s all peat moss. Before the ditch [Forsythe Creek], it was so deep, it was even wetter.” The family called this area “the oat patch.”

Dick described how there was a road east of Twin Sisters that went down to the back of the lower ranch. “It wasn’t much more than a cow track, but we drove it and hauled timber over it. [Uncle] Rome and I hauled timber down to the Kikionga Mine.”

Dick recalled that he always liked to work in that meadow because of its beauty, but it was challenging when shoveling snow. “I shoveled many a snowdrift. Just when you get it all shoveled out, the wind would come up and you’d have it all to do again.”

Rome and Pauline Wing’s family lived for twenty-two years on the lower ranch in what was once known as the ‘Halfway House.’ Rome would tend the cattle in the wintertime and help with hay. Once the house was vacant, vandals destroyed the structure, but a rock wall and the foundation of the house can still be seen as one drives along County Road 68 (Figure 7: Magnolia Road and Surroundings).

Figure 20 Ranch House (looking due North)

Figure 21: View from the Ranch House

Some of the Scates’ nearest neighbors lived two miles east of their home on property that was originally homesteaded in 1871, by James Carle. In 1899, the Barbers and Hoovers purchased Carle’s property and ran it as The Rocky Mountain Home Resort a/k/a Mountain House (Figure 22: Mountain House). Dick told that his mother had worked at the resort.

Dick said, “ It was considered the halfway house between Boulder and Blackhawk. The teams would come that far from Boulder, stay overnight, and then go on to Blackhawk. They had a regular boarding house then, although there weren’t many rooms. Many travelers would sleep in the wagons or in the barn.”

In 1907, the Hetzers bought the property from the Hoovers. Hetzers owned that property from 1907 until 1947. Dick remembered, “The lilac bush in front of the house has been there since the Hetzers were there. The buildings are all old. The Hetzers raised only angora goats. So, they did not share in the Scates’ work with cattle. Hetzers sold to the Hendricks in 1947. The Carle’s actual tiny homestead house still stands, immediately to the west of the former “Mountain House.”

Dick recalled some of the early homesteads in the area: Carle’s homestead house (Mountain House), Newton Hockaday’s house (Reynolds’ Ranch), our lower ranch house (Matthewson), the Best homestead, and the Winiger homestead (Figure 7: Magnolia Road and Surroundings). He said that they were all built fairly close to the same time, in the 1860s.” Still reminiscing about early homes on Magnolia, Dick said, “The log cabin, the Hockaday homestead house, is the oldest building on Magnolia. The log house was built first, and then the stone was built on, but about the same time.” It is said that the date the house was built is carved on the wall. That property, now known as Reynolds’ Ranch, is owned by Boulder Open Space and leased by the Reynolds family.

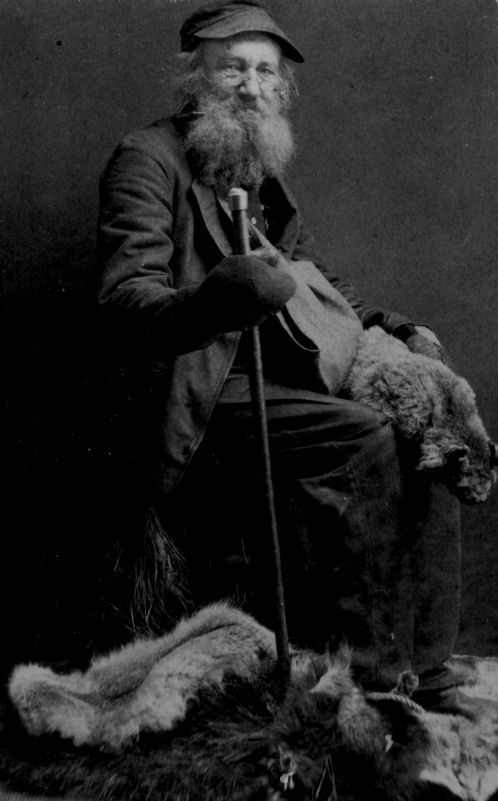

One of the really memorable characters on Magnolia Road lived on the Mountain House property in the early years. Dick recounted the stories he had heard: “There was an old barn up behind the house, and there was an old shack up behind there too, and the old guy who lived in the shack burnt himself up. He’s buried right there. His name was Dr. Bills. There are two stories about him. I wouldn’t have the least idea which is right. One was that he was a prominent doctor in Chicago at the time of the Chicago Fire. He got burnt out; his family all died; and he just came out here. The other story is that he came from back East somewhere and worked with the Indians, took some of their medicine, learned how the old medicine men worked. I don’t know which one was right.” In either case, Dr. Bills probably “lived like a hermit, trapping skunks, coyotes, and what have you. He lived in Bear Canyon before moving up here. When Mom’s family lived in Bear Canyon, Grandma got feeling real poorly, so they got Doc Bills to come and look her over. He said, ‘Oh, you’ll be all right. You take some of old Doc Bill’s little black pills.’ She didn’t die, so I guess they worked. He was a great guy for skunk oil” (Figure 23: Dr. Bills).

Figure 22: Mountain House

Figure 23: Dr. Bills

For more than eighty years, George Giggey, and his family before him, lived nearby and had many very close relationships with the Scates family. George shared this history of his family: “My parents [Charles Aden and Nancy Foster Giggey] were married in 1918, and they lived with Dad’s parents, George Leon and Mary “Mommy” Giggey, on Magnolia for a time. As the family told it, in 1919, they traveled to Dove Creek [in the southwest corner of Colorado] in a covered wagon. They homesteaded there on 160 acres. Before I was born, they lived in a ‘tent house.’ When the barn was built, my mother decided that the barn was better than the ‘tent house,’ so they moved into the barn.” George himself is known to joke that in 1931, he “was born in a barn near Dove Creek.” That is the truth. He was named George Leon Giggey after his granddad and an earlier relative.

George continued the family story, “When I was six years old, my family moved from Dove Creek to The Old Ranch on Magnolia Road [Hockaday’s Homestead]. We lived four years at that property.” Several owners later, the Reynolds bought The Old Ranch, and it is now known as The Reynolds’ Ranch and is part of Boulder County Open Space. The pond on the property, visible from Magnolia Road, is identified on detailed maps as “Giggey Lake.”

In the early 1940s, George’s dad bought the Winiger homestead (Figure 7: Magnolia Road and Surroundings). The family lived in the original 1861 Winiger log-and-chink homestead house which still can be seen at the intersection of County Road 97 and Colorado Highway 72. The homestead house’s roof collapsed during the great snowstorm of March 2003, when the weight of five feet of snow was too heavy for the 142-year-old building. Through the years, the Giggey family built other buildings on their property, and George and his wife, Blanche, raised their children and many grandchildren there. George continues to live there with some of his extended family.

The extended Giggey family owned a good deal of property in the Magnolia area. Dick Scates shared some additional history of the Giggey family; “George Giggey’s great-uncle, Del Giggey, bought Gaviness’ homestead rights and finished it up (Figure 7: Magnolia Road and Surroundings). Del lived in the old house there. My mother [Eva Scates] worked for Del and his wife when she was just a little girl. Like everyone else, they had a lot of kids and needed help with this and that.” George told us, “Del’s wife died in childbirth when their thirteenth child was born.”

Del Giggey’s property was owned next by Hardinger. Dick recalled, “The road grading was awfully good to old Hardinger’s. When the county road grader driver went by, why, he’d swing down in there.” We have learned that the driver was George Giggey himself. George worked for Boulder County, and he explained that his boss then, an elderly fellow, told him, “Take care of the older folks,” and that explains why George did grade or plow many older Magnolia residents’ roads and driveways, as he made his rounds. The Hardingers moved Del’s family’s house off its foundation and built their home over Del’s cellar. Dick noted that “there are a lot of springs [on that property]” and that “Hardinger built the pond that is there.” The current owner of that property, Joe Basco, tore down Del’s house when he built his addition to the Hardinger house.

George Giggey remained close to the Scates family. He and his own heavy equipment were often seen at the Scates’ Ranch. To this day, it is sometimes there. George said, “It seems like a part of that land.” When Dick and Edith grew older and were less able, he helped them out by doing what needed doing: feeding the animals, building fence, and doing chores. When Dick died, George took on more and more work around the ranch. Edith once told us, “George has been with us forever!”

In Edith’s later years, George would stop by every day. He cut the particular kind of firewood (aspen) that Edith preferred for the woodstove; and for many years, he was the one who made certain that Edith took her medication, and he put the prescription drops in her eyes when that was the doctor’s orders. The Scates had “taken care of him.” Later, George took care of them and their beloved home. Still, George is “caretaker” of the ranch, and he stops by every day.

Edith had such very warm memories of Ernie and May Betasso. “They lived up Sugarloaf Road. Theirs was a brick house on the right side of the road as you go up near the old Boulder Reservoir. The new water treatment plant on Sugarloaf was named The Betasso Water Treatment Plant,” Edith said proudly. Some of the Scates’ early neighbors (the Hetzers, for example) didn’t run cattle or have any cattle on the range, but the Betassos did. That made for a mighty and productive bond of friendship between the Edith and Dick Scates and Ernie and May Betasso. Edith and Dick would “change work” with them. They did cattle drives together and would help each other brand and vaccinate cattle. Edith stated firmly, “Anything to do with cattle, we worked together. For all that, you need extra help. My brother and I couldn’t do it, and Ernie and May couldn’t do it, so we just worked together.”

Edith mused that Ernie and his brother, Ray, who were contemporaries of Edith and Dick, “went to school at Silver Spruce [Elementary] School [at State Highway 119 and Magnolia Road, in Boulder Canyon]. Ray walked to Boulder to high school. Ernie didn’t go to high school, and neither did Dick.”

Edith loved May! She spoke of their great friendship, saying, “We got together a lot. We were best friends! She was a grand little person, and I just seemed to be so comfortable with her. We went shopping together and had lunch out.” May didn’t drive, so Edith “used to take her a lot of places.”

The Scates family worked hard to make a living. Everyone was needed to attend to many responsibilities on the ranch. Both adults and children were involved in tending the cattle and raising crops. Women took care of important domestic chores, such as laundry and preparing food, while the men usually would handle the ranch operations, such as plowing, cutting hay, clearing the fields, hunting, and transporting goods to and from town.

Edith learned from her mother how to perform household chores and did these throughout her life. But, from an early age, she also worked side by side with her brother, doing ranch work, such as milking the cows and digging potatoes. Perhaps this is why she adapted so readily as a young adult to handling a myriad of ranch responsibilities with Dick, such as clearing and tending to the fields, making fence, and driving cattle.

As Edith and Dick were growing up, they were responsible for milking three or four cows. “We just mostly [used the milk] for our own use, although we did sell some [butter and] cream. We did have to get the cows in, and milk them, and separate the milk.” Edith said, “Dick milked two to my one. I don’t know what the secret [was]. Maybe he was just stronger.”

Other childhood chores included splitting and carrying firewood, haying, and tending cattle. Edith recalled, “Riding [horses] wasn’t for play. We rode mostly after we were big enough to punch cows. Of course, you didn’t have to be very big.”

When Sherman’s eyesight began to fail, Dick (then somewhere between five and nine years old) had to take on tasks that required good eyesight: hunting and slaughtering. Explaining the probable cause of her dad’s failing vision, Edith said, “He did lots of blacksmith work. He shod horses, and then, he made the covering for wagon wheels. He didn’t use any [eye] protection, when looking into that bright [coal] flame. Now, you’d use very, very dark glasses to protect your eyes.” Sherman never went completely blind, but his vision was notably poor.

While they were children, Edith and Dick also helped with raising potatoes. They did a lot of work, from spring to fall: planting, weeding, digging, and hauling potatoes. Edith described digging out the potatoes. “Sometimes we used a digger, and sometimes we used a fork and just forked them out. We picked up the ones we were going to sell and put them in one basket [and separated them from the ones we were] going to eat. Even when we were quite little [eight or ten years old] why, we had to pick-up potatoes. That was a job, you know. Those half-bushel baskets were terribly hard for youngsters to do. Of course, very often some of the men, the older people, would empty the baskets into the potato sacks for us.”

In the evening, the adults would “go out with the horse and wagon, and then they’d take the sacks into the cellar and dump them into a bin. Later on, we’d sack them again and take them into Boulder and sell [them].” Potatoes were sold to [Cobb’s] livery stable on Walnut and 11th, Brady’s Grocery Store on Broadway and Spruce, and Joe’s Hamburgers. Potatoes were a cash crop for the Scates family until the 1930s, when the Dust Bowl deposited a fine yellow dust over everything, and subsequent potato crops were blighted.

Women played a vital role in handling the domestic tasks that allowed the ranch to run. Women would wash clothes no more than once a week. “On a nice day, [we would put the] old washing machine on the porch. We heated wash water in a boiler on the stove. Earlier, [we] had to [pump and] carry water from the well.” Edith and her mother made soap with lard and lye. The laundry was hung on a clothesline to dry. “If it was terribly cold, the clothes would freeze on the line.”

Edith recalled, “We got [ordered] a lot of [sewing material] out of the [Sears Roebuck] catalog. It was quite the shopping deal for us. [We] got nearly everything out of it, [including] clothes, shoes, and material.”

An important task of women was churning butter, which provided food both for the family to eat and to sell. “We had a tin churn with a dasher and later we got a glass churn. The time it takes to churn butter depends. At certain times of the year, you can churn butter in just a very few minutes, and I’ve seen it take an hour or two. It was harder to churn in the winter time, when [the cows] had just [been eating] dry feed.” Edith described how the family kept food cold before there were iceboxes: “Our milk and things we wanted cold would keep fairly well down in the spring [near the corral]. Of course, it was quite cool there.” The cream was sold in Boulder, and the milk was sold in Pinecliffe.

Edith and Dick’s mother, Eva, was a very hard-working woman. She enjoyed cooking and prided herself on having a good dinner for her family after their long workday. Reminiscing further, Edith told that her mother was creative and “just loved to quilt and crochet. And she dearly loved to make gardens, to can [food], and to do things like that. [She] loved to take care of other people.”

Large quantities of food had to be preserved to make sure everyone on the ranch could eat throughout the year. Since the men would go to town to get supplies only once a month or so, a lot of food had to be laid in. The Scates had a large garden. Edith recalled, “[We] canned and canned and canned. We didn’t have a deep freeze or anything then. We butchered our own beef, and even we canned that. I can remember, it used to be in August, when it was so beastly hot, when the beans [and peas] were good, and having to cook them in a boiler for eight hours. That was a hot old job.”

The Scates family raised chicken to eat, but they did sell some too. Chickens would generally come through the winter okay, but “occasionally, they’d get out in the snow and freeze a foot off. We had quite a few one-legged chickens.” When the winter was harsh, the hens wouldn’t lay as many eggs as during the rest of the year. The family also raised some pigs.

Although hunting contributed to the family’s supply of meat when Dick hunted rabbits, deer, and elk, Edith hated that animals were killed. Edith did not hunt. Once she said, they “had a whole bushel of rabbits. We’d raise ‘em and make pets of them and then we didn’t have the nerve to kill them. It’s silly, but then I don’t even like to have a chicken around that I have to kill.”

Dick described how he butchered beef. “We didn’t have refrigeration, so when we butchered beef, we had to use it up before it got to be warm weather. Of course, we canned, but we’d often have to take the ax out and chop a piece for dinner. I’ve cut steak with a double-bladed ax lots of times. You needed a pretty good whack to cut a steak when the beef was frozen solid. It’s not quite like cutting ice because the fibers held it together. We’d bring it in and cook it frozen.”

Women would can and make pies and jelly from handpicked strawberries, raspberries, chokecherries and huckleberries. According to her brother, Edith was “Queen of the Chokecherry” because she made the best jelly.

Edith described the challenges of baking on a wood stove. “It was not easy to bake on the old wood range, but we learned and managed. It was very hard to regulate your heat in a wood cook stove. You got so you knew how to do it. ‘Course, it’s much easier in a gas stove where you can set your heat. The old cook stove is up on the picnic grounds. Not much left of it [now].” Edith said, “My favorite baking was cookies, but [I also baked] some pies and cakes. We made our own bread all of the time. Then, we did make quite a bit of rhubarb pie. My favorite is lemon, but I always like [it] a little bit more tart. I put a little extra lemon juice in it. But, I really like lemon pie.”

A favorite pastime of friends and family was huckleberrying. Edith described a huckleberry as “ . . . really a blueberry, but much smaller and much stronger [in] taste. They have such a strong smell. I remember, we went huckleberrying and stayed all night in a cabin [near Tolland]. We had a washtub full of them. We were really sick from the smell of those huckleberries.” Collecting huckleberries was “really a job. [You] have to have rakes to get them you know? I have a couple of rakes left, that reach under the vines and pull off the berries. Oh what a job to clean ‘em, all the branches and leaves. You’d have to float ‘em all off.” One friend, Ernie Bettasso, showed his appreciation for the hard work of huckleberrying when he said, “Now remember, when you eat this pie, take little bites and chew it a long time.”

Edith told of wicks, mantles, and “the plant” during the 1920s and 1930s. “Well, for a long time, all you had was a kerosene lamp with a wick, you know? Then later, they [we] got those lanterns with mantles. They made a lot of noise, but they gave a really nice, bright light. Then, we got a little generated electricity. I suppose [it was] in the 1920s.” This made a huge difference in the quality of life at the ranch, and it allowed the family to have a radio. The ranch’s generator or “plant” was gas-powered and made an awful racket. It generated enough light for everyone to read newspapers, journals, and books.

Dick said, “When we decided we wanted a radio, Dad didn’t go for that kind of foolishness. He’d take in some homeless kids and look after them, but nothing like a radio.” Edith added, “So, Dick worked at the Kikionga Mine. Mom and I milked cows and sold cream and eggs, and [we] bought a radio. And you know, we didn’t have that radio a very little while, and Dad was the biggest fan of all. He was one of those to-bed–at-7-and-up-at-4-types, but ‘Amos and Andy’ came on later, and he stayed up for ‘Amos and Andy.’ They [white actors] were supposed to be black comedians, you know, before race became such an issue.” Later, the Scates bought a radio that had batteries they could recharge with “the plant.” Edith remembered, “While my dad was still alive, we had a radio that ran on batteries. We got static mostly, but we could get WLS in Chicago. I can’t remember who the announcer was, but he would say, ‘It’s a beautiful day in Chicago, the wind is blowing, and it’s four below zero.’ We’d get ‘The Grand Ole Opry’ from Chicago. We got some world and local news. Of course, news didn’t travel as fast at that time, but it was much easier to keep current after you got a radio.”

Dick elaborated on the change electricity made to the ranch. “We take it for granted now, but when we think, before that, we had a power plant — that was a headache.What a change electricity was! We got electricity here after WW II (about 1948). We brought the line over from Hardinger’s. I had a friend on the REA [Rural Electrification Act] board at the time, so they said they’d do it. They said, ‘but you go back and talk to Public Service. Well, I knew the guy at Public Service, so I took the papers down and [threw] them on his desk and said, ‘Well, can you beat that?’ He looked at the papers and said, ‘I can’t beat it, but I’ll do my best to equal it!’ We cut the right of way. I thought we’d be waiting on Public Service for the next two years. We’d just got started [cutting] down over the hill from Hardinger’s place and looked back, and there Public Service was, setting poles.” To keep ahead of the Public Service crew, Dick and his friends “had to work like slaves.”

Edith described her brother: “Dick worked hard in school and got good grades, but he didn’t like it one minute. He enjoyed life, and he saw the funny side of a lot of things. [He was] a person with a good disposition. He was just a little taller than me. I am five feet, two inches. Dick was five feet, six or seven inches”. The war was on, and he went to register. He was going to enlist. The doc or whoever was registering them said, ‘You’ll do more good raising crops and raising food than you would do in the Army.’ They didn’t take him, because he was grazing cattle and raising potatoes.”

Edith described her father as quite strict and domineering, especially with his son. Dick had part of his father’s disposition, and so they clashed quite a bit. When Dick went out to live in Arizona for a year or so, Sherman realized he couldn’t manage the ranch alone. So, Sherman asked his wife, Eva, to write to their son to ask him to return to run the ranch with him as a partner. Dick did so, and Edith recalled, “It worked out okay.” She said that her father must have realized that “he would have to be more considerate if he was to have help from his children.” Dick gave his own account, “I worked away most of the time until Dad died. The last eight years he lived, I stayed here most of the time to help run the ranch or get in the way. I just about did all the work. Of course, he did the bossing, which I could have done without. He died in ‘40; I was thirty-two.”

Around the time when her father became ill and after he died, Edith became an even more integral part of general ranch operations than before. Edith and Dick often would get around by horseback. “It was quite a job putting up hay and raking. Typical day chores were sawing wood, hauling hay, making fence, plowing, or moving cattle.” Edith recalled how they worked together. “I would drop the potatoes and he’d come along and cover them up. When we were putting up hay, why, he mowed and I did the raking. Then, he’d bale, and we’d load the hay. I did that up to just a few years ago.”

Edith performed some tasks that were not traditional for women to do. She chuckled as she remembered how she and her brother cleared rocks from the hay fields. They would blow the rocks out with dynamite. The fuse had to be long enough so that they could get out of the way in time. Dick would light the fuse, and they would have to run so the rocks wouldn’t hit them. “Well, it was our job, and we did it without thinking. Of course, we enjoyed nearly everything on the ranch.”

Maintaining the fence around the ranch was a huge task that required attention every spring after the damaging wind and snow of winter, as well as damage caused by elk. Edith and Dick repaired the fence together, including digging postholes with a spade and a digging bar. They would look for burned pine trees to make fence posts. Wood is pitchy if it is from trees that have been partially burnt, making it harder and more resistant to rot. Edith could split a seven-foot pitch log with a double-bitted ax. She would first split it into halves, then split into quarters to make posts.

The men “hauled potatoes and coal mine props to the mines near Louisville, then purchased staple foods to haul home, i.e. 500 pounds of sugar and 1,000 pounds of flour.” Dick recalled, “One of the things we used to do in the wintertime to make a little money was cutting mine timber and hauling it to Boulder. We’d cut green timber around here and haul the logs down. We sold to a guy in Boulder who also sold coal. He’d weigh it up and pay us, then he’d haul it out to Louisville. We’d cut with a two-man saw and ax, cutting trees over sixteen feet so the tops were about four inches minimum, mostly lodge pole.” Edith described a coal-mine prop. “Well, it’s just a timber they put in to keep the mine from caving in, so the people could go down in and get the ore out . . . They used to haul it out, usually by those big buckets. They would pick it over and pick out the richest ore.”

George Seal (the uncle Sherman came to live with when he was a teen) worked in the mines at Magnolia. The following were mining claims owned by George Seal: Black Tiger Lode (1877), Croesus Lode (1880), Audophone Lode (1885), Potosi (1885), and the Recluse Mill site (1888). Edith said, “My father didn’t work the mines. Dick worked at Kikionga some, but not a great deal.” Now there is an overlook on top of the Kikionga site just below the four-mile marker (Figure 24: Kikionga Mine.